For lawyers in private practice, the search for clients is a never-ending quest. Traditional advertising, Google AdWords, logo-emblazoned swag, direct mail campaigns, little league jerseys, conference displays, Elks Club meetings – it’s that Glengarry Glen Ross compulsion to get the new leads, hopefully without the profanity.[1]

For all the time lawyers spend trying to get the calls and website hits, it’s surprising that there is so much debate about what to do with prospective clients once you get them on the line or in your email. Drop by a bar association listserv, the Maximum Lawyer Facebook group, or some other forum, and you will find lawyers frequently trading tactics and techniques for reeling in new clients. How much information should you obtain in the first conversation? Should a lawyer or nonlawyer handle the call? When do you do the conflicts check? Free consults or paid? One size does not fit all.

Starting Point. Rule 1.18(a) of the Rules of Professional Conduct defines a “prospective client” as “A person who consults with a lawyer about the possibility of forming a client-lawyer relationship with respect to a matter.” That’s pretty broad. A “consultation” with a prospective client (PC) could occur anywhere, at any time. It could be in a Zoom breakout room or at a July 4th socially distanced picnic. It doesn’t matter that the PC has not yet paid you any money or signed a retainer.

The reason the Rules define a PC is to grant those tire-kickers and rate-shoppers limited confidentiality rights. Rule 1.18(b) says that the information you learn in “the consultation,” even if they never darken your door again, cannot be used or revealed except as otherwise permitted by the Rules. It is not clear from these two subparts alone what constitutes a “consultation” that qualifies for this protection. In classic lawyer style, the comments say that some interactions may not rise to the level of a consultation but it “depends on the circumstances.” Some types of contact are excluded. For example, people who unilaterally dump their TMI on you in an unsolicited e-mail or voicemail message have not had a “consultation.” But if you invite contact, say through a form on your website, it might be wise to warn PCs that there is no attorney-client relationship until you say there is.

The upshot of this requirement to protect PCs’ confidential information is that lawyers need to make sure that the names of PCs find their way into the lawyer’s conflicts database. If you’re conflict avoidant, that may sound a little daunting. But Rule 1.18(c) provides a limited safety valve. It says that if the information you receive from a PC would not be “significantly harmful” to the PC if you represented someone adverse to the PC, then you will not be conflicted out of representing a future adverse party.

Intakes vs. Consultations. Which brings us to the practical questions of how lawyers should handle conversations with PCs. At one end of the spectrum, you could have an “screening” process, which we’ll define here as a relatively brief contact in which the PC provides enough identifying information to perform a conflict check and a minimal synopsis of their situation that gives the lawyer some hints as to whether the lawyer might be interested in representing the PC. The information gathered is so minimal that you probably do not have to worry about whether you have had a “consultation” under Rule 1.18 because there is so little information to protect. The larger the firm, the more necessary it may be to conduct an “screening” as a prelude to a consultation.

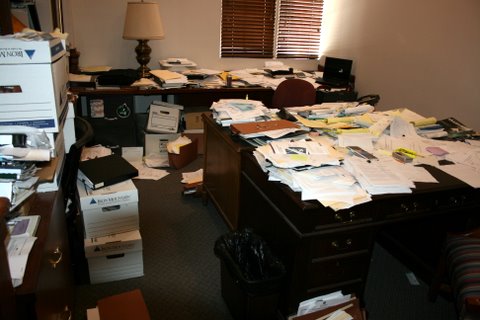

Screening limits conflicts issues but the problem that remains is how you close the deal. You have got to convince the client that they should hire you. That likely requires a longer conversation in which the lawyer demonstrates their winning personality, their empathy for the client’s personal situation, and makes their sales pitch. After all, the leads are not worth much if you cannot convert them. There are some lawyers who advocate for keeping the client on the phone as long as possible because they find it leads to a higher conversion rate.[2] Obviously, the more information you gather, the greater the possibility of conflicting the firm out of a future representation even if the PC does not hire you.

Free vs. Paid. In some practice areas, lawyers have to sift through a high volume of PC calls. The path to converting those leads may be through free in-person or Zoom meetings, but long initial consultations collectively consume a tremendous amount of lawyer or staff time and they do not all convert: sometimes it turns out that the PC was really just looking for free advice. Or the opposite problem occurs: the lawyer schedules meetings but the clients do not show up.

One way to narrow the funnel to more serious PCs is to charge an initial consultation fee. The fee might be at or below your usual hourly rate, designed to get the PC’s buy-in and relieve you of feeling like a chump if you provide good advice during that consultation. Whether it works for your practice may turn on the type of law. Criminal law, personal injury, and workers compensation attorneys are not likely to charge for an initial consultation. Paid consultations can work for business clients, family law, and other areas in which the lawyer can both give advice and encourage the PC to retain them at the same time. Be flexible. You can offer paid consultations when you are busy and switch back to free when work slows down.

At the end of the day, just getting the new leads is not enough. Remember your ABCs: Always. Be. Closing.

(Originally published in the May 2021 issue of Hennepin Lawyer)

[1] David Mamet wrote the Pulitzer Prize winning play (1984) and the screenplay for Glengarry Glen Ross (1992), which was kind of a mash up of “Waiting for Godot” and a real estate sales agency. Truth be told, it’s one of the only movies I’ve ever walked out on.

[2] Arizona lawyer Billie Tarascio has an online “Intake Training Course” that teaches her philosophy of the lengthy intake or consultation. See https://modernlawpractice.com/course/intake-for-law-firms/ (last visited Mar. 31, 2021).

There is a good deal of postulating in the blogosphere about the types of ethical trouble a lawyer can get into by using social media. The nattering nabobs of negativism warn us to be careful when using social media like

There is a good deal of postulating in the blogosphere about the types of ethical trouble a lawyer can get into by using social media. The nattering nabobs of negativism warn us to be careful when using social media like