Thanks to COVID-19, nearly every lawyer has had a taste of working “remotely,” i.e. physically severed from the credenzas, file cabinets, and rolling stacks of shelves that house their paper files. Suddenly, the “file” is everywhere: electronic documents that used to reside only on an office computer or server now may have been saved on a home laptop; letters to opposing counsel are mixed in with e-mails; and the few critical paper documents that have been scanned by your skeleton office staff and sent to you by e-mail seem to have since disappeared from your computer. Welcome to the deep end of the pool.

Not only are you having trouble keeping track of where all the pieces of your file are but, someday, a client is going to ask you for a complete copy of their file, which you are required to provide to them under Rules 1.15(c)(4) and 1.16(d) and (e), Minnesota Rules of Professional Conduct (MRPC). Failing to provide the client with a copy of their file is a very common basis for an ethics complaint. So, this seems like a good time to talk about how to manage an electronic client file, before a second or third wave of COVID-19 sends us all back home again.

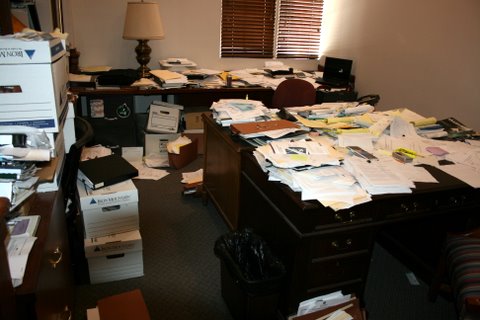

File Naming. Electronic files need to be organized just like paper files. In an electronic file, every document gets a name, not unlike the “pleadings index” one might find in a litigator’s file. One of my biggest pet peeves is when a lawyer e-mails me a document titled “Scan0001,” the default name put on the document by the scanner. Not only is it impossible for me to figure out what the document is without opening it but the person who sent to me also cannot tell. A folder of documents titled “Scan0001,” “Scann0002,” and “Jones letter” is like a large random pile of documents sitting on the edge of a desk.

Unless you are using sophisticated document-management software, every file name should start with a client identifier, such as a file number, last name, etc. That way, when a document inevitably ends up in the wrong folder, you can still search your computer for all documents with that client identifier.

Next, I like to identify the type of document: ORD (order), PLD (pleading), LTR (letter), and so on. That way, documents of a similar type are grouped together when I look at the folder contents.

All documents should be dated, with the year first, e.g. 2020.0801. Use the whole year, not just the last two digits, at least until 2032. Avoid inserting the month first (e.g. 0801.2020), which will group all the July documents together over multiple years, making it more difficult to find what you are looking for. Similarly, if you write out the month (August 01.2020), then August documents will appear before January documents.

Putting it all together, a letter for client Smith might be named “123.SMI.LTR.2020.0801.FINAL.to E. Kagan re counteroffer.pdf.” Even if you later cannot recall what exactly you named the document, searching for “SMI.LTR.2020” should reveal all the letters you wrote this year for that client. Of course, you can come up with your own naming system but it should have these elements.

Drafts and Finals. In an ethics investigation focused on whether the lawyer communicated with the client, it is not very convincing for a lawyer to produce a copy of a Word document, unsigned, no letterhead, with the date field updated to the date the lawyer most recently printed the document. Think of all Word documents as drafts. Final documents, such as pleadings, letters, contracts, etc., have signatures on them and should be preserved as PDFs.[1]

Preserving emails. Two guidelines about preserving e-mails. First, always save attachments to a document folder, renaming them as above or using your own system. Hunting through old e-mails for a poorly-labeled attachment is mind numbing. Second, move client e-mails from your inbox to a dedicated client folder. At the end of the representation, save them all as either one large text file or as PDFs. If you are not sure how, ask the Googles.

File notes. Except for a few narrow situations, your handwritten or typewritten notes of your conversations with clients, opposing counsel, witnesses, etc., are part of the client file. See Rule 1.16(e). Yes, your notes may be privileged or work product but nearly always the client owns that privilege or work product. Preserve the notes at the end of the representation by either scanning them (if handwritten) or saving them to a text file or PDF if typewritten.

Invoices. It may seem obvious that invoices are part of the client’s file but often the invoices are maintained through software that is distinct from the lawyer’s document folder system. Routinely preserve PDFs of invoices and save them to the client’s folder.

The good news is that providing a client with an electronic version of their file is much faster and easier than spending half a day in front of a copy machine pulling out staples and clearing copier jams. Another bonus is that attorneys do not have an obligation to maintain paper copies of client files, except for original documents, as long as the client will not in any way be prejudiced by the lack of a paper file.[2]

By the time the third wave comes, you are going to wonder why you bothered with all those paper files for so long.

[1] This concept attributed to Sam Glover.

[2] See Virginia Legal Ethics Opinion 1818 (Sept. 30, 2005).

This article was originally published in the Hennepin Lawyer, July 2020, under the title “Managing All the Pieces.”

Tuning in to the live tweets last week from the opening of the Association of Continuing Legal Education conference in New York City (it may sound dull, but they are a hard partying group!), there was much talk at the plenary session about the allegedly irrevocable changes occurring in the legal profession because of the fallout from the Great Recession. Familiar themes: hourly billing is evil, the leveraged-associate model is on its way out,

Tuning in to the live tweets last week from the opening of the Association of Continuing Legal Education conference in New York City (it may sound dull, but they are a hard partying group!), there was much talk at the plenary session about the allegedly irrevocable changes occurring in the legal profession because of the fallout from the Great Recession. Familiar themes: hourly billing is evil, the leveraged-associate model is on its way out,  As I surf around the blawgosphere, I have noticed that it seems to be in vogue for

As I surf around the blawgosphere, I have noticed that it seems to be in vogue for